Peat, better the devil you know? Or the one you don’t?

If you work in horticulture, there is no getting away from the fact that sustainability has become a nationwide public priority. Whether this is recyclable plastics or responsibly sourced growing medias, environmental lobbying will have stronger influence on policy, just as we are beginning to see in the latest agricultural bill with ‘public money for public goods’ alongside the most recent letter addressed to the Environment Secretary from environmental groups and celebrity gardener Monty Don aiming to ban total use of peat in all sectors by 2025.

The paragraphs below aim to give some depth and figures behind the peat industry, its environmental impacts and what are the potential alternatives. Although horticulture does tend to receive the brunt from opposition groups and media publications, it is worth noting that the vast majority of peat is actually sold into amenity use as soil improvers (AHDB,2015), which is much more suitable for substitution.

What is the current picture?

Worldwide there is estimated to be 407 million hectares (Ha) of peatland (blanket bogs, wetlands, fens, forests), of this around 15%, 58.5 million Ha have been drained for some purpose; typically urbanisation and agriculture, whilst 85% remains in its natural state. There are 51.5 million Ha of peatlands located in Europe, of which the UK equates for around 2.3 million Ha.

British bogs equate for 13% of the worlds blanket bog and 60% of the UK peatland is located within Scotland. In conjunction with the current issue surrounding permafrost melt gaining increased news coverage, the importance of maintaining peatlands as a carbon sink alongside their preservation is of global importance and a strong political driver as the UK pledges to have a net zero carbon output by 2050.

This news however is nothing new, since 2000 total peat extraction in the UK has halved, with less than half of 1% of the total peatland areas in the UK used for extraction.

The most recent development on peat extraction has been in Southern Ireland, previously being the key supplier of peat to the UK market. Due to incorrect implementation of EU planning and licensing regulations nearly all peat extraction has been temporarily ceased. This even includes Bord na Mona, the government owned and run Irish Peat Board, who were one of the largest producers of raw peat in Europe (correct as of Nov 2020). It is still uncertain that if the bureaucratic hurdles of planning and licensing are overcome whether there will be the political will to restart. There are an estimated 6,600 jobs directly related and 11,000 indirectly to the peat industry in rural Ireland.

So, who are the remaining main ‘culprits’ for abstracted peat?

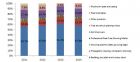

Worldwide only 10% of peat extracted is used for horticulture in any form including the hobby market. Of this 10% (roughly 4 million cubic meters) in the UK, 70% is sold into the retail markets for products such as 70Lt bagged John Innes garden mixes (typically containing 50-60% raw peat), 1-2% gets exported and the remaining 28-29% is used for professional use. Although old data, the chart gives a good indication of the proportional split of peat usage amongst professional users.

Why do we use Peat in horticulture in the first place?

In fact, we do not use peat for everything, coir is the standard for soft fruit production, rockwool for protected salads and some products can be grown hydroponically, but in commercial horticulture we do use it a lot; why?

Peat becomes the main component for containerised and growing media mixtures in commercial production when compared with other organic materials due to several physical properties such as high porosity, water holding capacity (WHC), slow degradation ratio, low bulk density and it generally being weed free. It also has good chemical properties like high cation exchange capacity (CEC), easily adjustable pH and low microbiology resulting in a uniform and uniquely reliable substrate.

A balanced argument or an intangible attack on the peat industry?

As abstraction from peatlands is somewhat of an emotive subject, there are social implications to consider.

There are much more detrimental recreational industries in regard to CO2 emissions, such as the aviation industry. For example, the same amount of CO2 per Ha will be released per annum from a German peat extraction site as 3 passengers flying one way from London to New York.

On the flip side campaigners could argue that an unfettered peat bog absorbs large quantities of CO2 continuously, whereas degraded and commercial bogs do still release large quantities of CO2 emissions that are inarguably negatively impacting the environment.

In practice, drained peatlands located mainly on raised bogs do become major sources of greenhouse gases. Small disruptions to the hydrology of peatlands can upset the balance from carbon sink to carbon source, neighbouring areas of bog within the same hydrological unit can become degraded as a result of the drastically lowered water table. Lowered water tables allow oxygen to penetrate the formerly permanently waterlogged peat allowing rapid decomposition. Well managed peat extraction sites emit on average 3.13t C02/Ha/Yr for German extracted Black Peat and 8.05t C02/Ha/Yr for Lithuanian White Peat.

In layman’s terms this is equivalent to driving a medium sized diesel car 12,500 miles per year for 1 Ha/Yr of Black Peat and 32,000 miles per year for 1 Ha/Yr White Peat.

What are the alternatives to Peat?

Bearing in mind most of the peat usage in the UK is for amenity gardener use, most peat use in retail can readily be replaced by more sustainable alternatives. The growing media industry has developed high quality products often using composted green wastes, for most gardening uses the physical and chemical composition of these products

would be ‘fit for purpose’.

Based on the current situation, in commercial horticulture working without peat in growing medias would lead to a supply gap, as alternative substrate constituents are not available in sufficient quantities.

For seedling and module propagation alongside ericaceous plants, we would also find several agronomic challenges. The main alternatives are coir, wood-fibre, bark, green waste and anaerobic digestate. There are plenty of others that have been used over the years with success such as bracken and wool, but currently these do not meet the availability and cost requirements for large scale adoption.

The use of wood-based and coir ingredients has increased consistently over the last 10 years, with green compost and bark accounting for similar volumes as a partner for peat reduced mixes. Up to 30% of growing mediums containing wood fibres or green waste materials often have little effect on plant vigour and can in fact improve structural properties of the substrate, helping avoid waterlogging, bacterial infections and fibrous root formation.

Too high proportions of woody fibres can cause nitrogen drawdown, reducing N availability to plants and a stunted, pale green crop. It is important to buffer woody fibres with additional Nitrogen to compensate (typically 100g/34% N/per 100L wood fibres/CuM.) Over time the wood fibres will naturally decompose with the assistance of moisture, oxygen and soil microorganisms to be available to the plant, however the benefit will greatly depend on the length of growing cycles.

Alternative substrates however are not without their pitfalls.

Alternative substrates however are not without their pitfalls. Coir (coir pith/peat/dust/meal) is a brown, sawdust-like material that looks similar to dry peat moss. Most coir used in horticulture comes from large coconut fibre processing mills located in Sri Lanka and India. An additional calculation therefore should be made as to the true carbon emissions contribution of transport and shipping.

Processing coir also requires a significant amount of fresh water and in some areas like India, drinking water is already in short supply. It takes 300 to 600 litres of water to wash one cubic meter of coir pith. The result is polluted water that impacts the environment. If legislation imposes true carbon footprint taxation on the importer of such products the question of economic viability and social acceptance of ‘carbon heavy’ products remains.

What do we need to learn about managing the alternatives?

When using peat alternative growing substrates, growers will need to alter their irrigation, nutrition application and stock replenishment practices in accordance with specific materials being used. For example, organic peat free mixes are best used fresh as speed of decomposition and nutrient release is significantly quicker than traditional peat-based mixes.

Higher proportions of wood fibres in mixes also require additional nitrogen to maintain the immediately available nitrogen, buffering drawdown into the highly lignified material. Green waste materials offer a great byproduct and locally available option for most growers, however there are still limitations to overcome regarding consistency (dependant on time of year and green waste used), contaminants and heavy metals.

Professional users moving to higher proportions of white peat than black peat will be aware of the alteration needed when it comes to substrate wetting, re-wetting and Available Water Capacity (AWC). This reasoning also applies when using alternative substrate materials available.

Coir tends to have high levels of potassium and low levels of calcium, therefore as a season progresses, fertilisation will closely need to be monitored through ‘soil’ testing. This report could go into a long list of agronomic considerations, if you are interested or have any questions on a particular scenario it is best to contact one of the DEJEX technical agronomists to help with specifics.

As an industry representative, what can be concluded?

We are all responsible for our own reduction in CO2 emissions, whether that be personally or professionally. Most commercial growers even using a “peat” based substrate will have already worked to reduce the peat content by 10-30%. A couple of factors regarding this to remember in respect to CO2 emissions:

- The alternatives to peat; coir, wood-fibre, bark, green waste are by no means Carbon neutral.

- The worst thing that can happen to an already commercialised peat bog is ceasing peat extraction.

The first point is obvious, whether it is shipping coir from India and Sri Lanka or using heat and pressure to process some of the other materials they are all reasonably CO2 hungry. Let us look at the second point which seems counterintuitive. Surely the best thing would be to cease extraction and rewet the bog? As always it comes down to money, currently most countries where peat extraction takes place have strict caveats to planning in place meaning producers have to outlay a percentage of money over the 20-50 year lifespan of the project to rewet and thereafter manage these bogs. If commercial businesses are forced to stop extraction immediately, they could walk away from the bogs and their commitments to rehabilitate them – leaving CO2 output high ad-infinitum.

Having unsubstantiated demands asked of the government to completely ban peat with no suggestion of substitution materials for the horticultural industry is dangerous and causes misguidance to those in power. To claim that the voluntary initiative to reduce peat usage “has fallen grievously short” (Monty Don, 2020) is I am sure an insult to many within the industry. Over the last 6 years, the amount of peat traded within the UK has halved from 4 million CuM to 2 million CuM.

We should also remember that peat being used to grow plants such as perennials, can capture more CO2 than the amount released from the associated volume of peat extracted. The peat that is being used in commercial horticulture, often is to produce food, something that should be last on the CO2 targeting list, potentially compromising domestic production.

As an industry, if there was to become a comparable media available that could match the qualities of peat, at the correct price point and was much more sustainably sourced then growers would jump at the opportunity to use these products as retail demand and social responsibility would welcome such a change.

Although significant investment is being made in finding such materials and cost-effective production methods, the UK is not currently at this stage. We think there is further work that needs to be done in green waste recycling. If green waste constituents can be segregated and mulched more consistently and reliably then we can see increased opportunities to incorporate at a higher rate in certain mixes.

So, are you better with the devil you know or the one you don’t when it comes to Peat? Well as most things it comes own to a compromise, but in some sectors of commercial horticulture to continue with volumes, quality and price expectations we may have to continue to do a deal with the devil for a little longer yet.